|

Brought

to you by 1% Productions

How

the two unsung heroes of the Omaha music scene took their love of

beautifully obscure music and made it into a business.

story by tim mcmahan

|

|

|

Lazy-i: July 13, 2003

|

It's

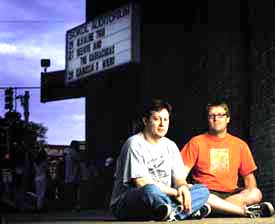

a typical night at the Sokol Underground, and you can tell by the

smug, satisfied look in their eyes that the 1% Productions guys

have already started counting their money.

The

evening began with question marks that were typed months earlier

when the duo booked the band about to take the stage -- a sleepy,

slightly-depressed singer songwriter that goes by the name Cat Power.

Marc Leibowitz, the savvy, bare-knuckle fireplug of a guy who looks

like a stockier version of Kieran Culkin, was never too keen on

booking the band in the first place. The guarantee -- the amount

of money promised to the performer regardless of how many people

come to the show -- seemed too high, especially for a market like

Omaha that worships tired Freedom Rock bands, where there are no

radio stations cool enough to play a marginal, under-the-radar act

like Cat Power in the first place.

They would have passed,

except that the other half of 1% Productions, the red-haired, bespeckled

Jim Johnson, who looks like he walked off the pages of a Dan Clowes

comic, adores Cat Power and the act's sultry singer/songwriter,

Chan Marshall.

So, like most shows the

duo books, they weighed their costs, their necessary ticket price

($13, about twice the usual going rate for a show to a Sokol Underground),

considered the "cool factor" and rolled the bones.

This time the dice came

up '7.' The club, which has a posted capacity of 315, was sold out.

Stylish early 20s hipsters with their shiny black shoes and ironic

slacks stood elbow-to-elbow with indie-rock-slacker youth wearing

T-shirts bearing obscure band names and beat-up Chuck Taylors, all

lost in a fog of dirty cigarette smoke.

Sokol Underground is

little more than the basement for the much more respectable Sokol

Auditorium at 13th & Martha. With its cigarette-stained linoleum

floor, red-shaded ceiling lights and metal poles stuck in the most

inconvenient places, there is nothing interesting or attractive

about the venue. But for the arty, nonconformist youth of Omaha,

The Underground is the home of the city's indie rock explosion.

All of the nationally renowned Saddle Creek bands cut their teeth

down there. And some of indie music's most "popular" acts

have crossed its plywood stage, all brought to you by the discernable

entrepreneurial duo known as 1% Productions.

They'll be the first

to tell you that their business has little to do with making money.

They've barely broken even over the six years that they've been

operating as independent music promoters. There is nothing lucrative

about bringing critically lauded but virtually unknown, uncommercial

bands to Omaha, such as Spoon, Tristeza, Death Cab for Cutie, Mates

of State, Guided by Voices, Low, Rye Coalition, Interpol and dozens

of others that are among the most creative, most interesting, and

most unknown acts working in the music today.

"I look at this

as a paying hobby," Leibowitz says. "We take risks. We're

not making crazy money. I can't make a mortgage payment on what

I make operating 1%. We lose money some nights. But other nights

I get paid to see the bands that I love. Making a little money is

just an added benefit."

"The reason we started

this was because the bands we wanted to see weren't coming here,"

Johnson said. "And if we hadn't stepped in, they probably never

would have."

|

|

|

One

Percent got its start in October 1997. Johnson already had been

booking bands into the legendary all-ages venue The Cog Factory.

Leibowitz had just moved back to Omaha after getting a degree in

management information systems from UT Austin. The two had known

each other for years, even talked about opening their own club some

day.

Ariann Anderson, then

lead singer of the band Echo Farm, had contacted Johnson about booking

her idol, folkster Ani DiFranco, into Sokol Auditorium. Though a

known commodity in the indie world, DiFranco was far from a household

name in '97 and no one locally was willing to risk fronting her

modest guarantee.

Johnson talked it over

with Leibowitz. "Ariann had connections to do the show, but

didn't have the money," Leibowitz said. "We crunched the

numbers, talked to the people at Sokol and decided to put up the

cash ourselves."

In addition to handling

the hall and the money, Johnson and Leibowitz also took care of

the show's promotion, which consisted of posters, ads in The Reader

and word of mouth. "It also helped that Ani was on the cover

of Spin Magazine about two weeks after we signed the contract,"

Leibowitz said.

The show that no promoter

in the city would touch sold out in advance -- a feat that 1% would

never repeat. "It was a helluva way to start," Leibowitz

said. "It went off without a hitch."

But it was a short-lived

victory. The next "big" show -- a Jayhawks gig six months

later at Sokol Underground -- bombed. By then, Johnson (who was

Leibowitz's roommate) had already dropped out of 1% in an effort

to keep their friendship alive, leaving Leibowitz to suffer the

loss alone.

"When we did the

Ani show, the agent had coached us," Leibowitz said. "He

explained the contracts, the advertising, everything. The Jayhawks'

guy, who had dealt with the Ranch Bowl in the past, let me get in

over my head. When it came down to negotiations, he took the hard

line and I ended up losing $1,000 -- the biggest hit we've ever

taken. Half the profit of the Ani show paid for my loss at The Jayhawks.

Now any show where we lose money, we think of Ani."

Leibowitz survived the

Jayhawks setback and put on 22 more shows at Sokol Underground throughout

'99 and 2000, including such influential indie bands as The Dismemberment

Plan, Guided by Voices, Built to Spill, Pedro the Lion, and Saddle

Creek acts Bright Eyes, Cursive and the Faint. He was on a roll

until his dot-com job went bust and talks began surfacing about

closing Sokol Underground and turning the basement into offices.

Leibowitz got a job in

Chapel Hill, but quickly missed his old hobby, which he didn't have

a chance to pursue in North Carolina. When word came that Sokol

Underground would continue after all, he moved back to Omaha in

August 2001 and reestablished his partnership with Johnson, who

makes a living as a salesman for an auto body supply house. One

Percent Productions' second chapter began with a Wesley Willis show

Feb. 5, 2002, and the duo hasn't looked back since.

|

Chan

Marshall a.k.a Cat Power at Sokol Underground.

|

"We

lose money some nights. But other nights I get paid to see

the bands that I love."

|

|

|

|

The crowd

surges the merch table after

a performance at Sokol Underground.

|

"You

can put in all the effort, skill and time, but it doesn't

mean you're going to have a successful show."

|

|

|

How

have they managed to survive all these years?

They say there are three

things an independent promoter needs to survive in a business that's

littered with the busted bank accounts of well-intentioned entrepreneurs:

Connections to a club, money and knowledge if a show will draw well.

"You have to have

all three or it won't work," Leibowitz said. "You can

put in all the effort, skill and time, but it doesn't mean you're

going to have a successful show. It's a calculated risk, but if

you know about the industry, it doesn't have to be."

Let's start with the

club.

Leibowitz first forged

his relationship with the Sokol Organization with the Jayhawks debacle.

"Instead of renting the hall, I said why don't I pay you a

percentage of the door," he said. "We bargained and created

the 1% / Sokol deal."

It's a sweet deal for

the Sokol organization, which gets to keep all the bar business

taken in at the shows. Club owners will tell you that booze money

is good insurance for shows that are on the bubble of covering the

guarantee, but it's tentative insurance at best. "If you have

a show that tanks -- that draws 50 people -- you're still only going

to bring in maybe $250 in bar sales, and you still have to pay a

bartender."

From a money standpoint,

as an independent promoter, 1%'s expenses are relatively minimal

and include the band's guarantee, advertising and other promotional

costs, and any rental fees. "Yes, we're gambling on shows,

but the company is just Jim and I," Leibowitz said. "If

we owned a club, we'd get the bar money, but it's not the end all.

Clubs have mortgage payments, payroll and lots of other expenses.

If you could lose money on the door and make it up with the bar,

every bar in town would be doing live shows."

He said the decision

to do a show ultimately comes down to a break-even number based

on ticket price and attendance. The ticket price is derived from

the possible attendance, along with the band's guarantee and other

expenses. Leibowitz said contracts are drawn up with national bands

that break down the compensation between both parties beyond expenses.

It can be quite a math project.

Knowing if an artist

will draw well, however, is more of an art than a science. Although

Leibowitz and Johnson have been following music for years, they

still rely on friends in the Omaha music scene to advise them on

whether a band will draw or be a dud. "For several years, we

referred to Roger Lewis (drummer for The Good Life). Now we talk

to Chris Harding who works at (record store) Drastic Plastic, and

Eric Ziegler and Marq Manner at Homer's."

"We're getting older,"

Johnson said. "It's hard to always know what the kids are into."

A fourth key to success

is building relationships with national agents who book the bands'

tours. Though a bidding system is uses for larger touring acts,

having a relationship with an agent can help grease the skids and

get exclusive offerings. That means sometimes booking bands that

won't necessarily be profitable to get to the profitable ones, Leibowitz

said.

"For example, we've

done shows with the agent who handles Built to Spill, Imperial Teen

and Mike Watt. We knew that Imperial Teen wouldn't do well, but

we knew that they wouldn't offer the others unless we took it."

As it turned out, the

Imperial Teen show was the second-worst show 1% has ever booked,

but they made it up and then some with the other two.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

This

is where the competition comes into play. "The Ranch Bowl would

like to take all of our shows," Leibowitz said, adding that two

recent Ranch Bowl gigs -- Vue and Small Brown Bike -- were shows 1%

would have booked.

"The Ranch Bowl

is one of the reasons why I got into this business in the first

place," Johnson said. "I went there to see Camper Van

Beethoven and was treated like shit by their Gestapo security guards."

That was years ago when

the Ranch Bowl was under different management. The club has always

insisted it's not in competition with 1% Productions.

Neither is The Music

Box. In fact, 1% and The Music Box recently joined forces to host

Luna, John Doe and God Speed You Black Emperor at the Box. The two

also are co-promoting a few upcoming shows at Sokol Auditorium,

including Big Head Todd and the Monsters July 10, and The Jayhawks

and The Thorns July 13.

J. Rankin, who runs The

Music Box, said the partnership with 1 % benefits both parties.

He turned to the duo out of necessity when seeking a venue larger

than his own club. With a capacity of 1,500, Sokol Auditorium was

a perfect option.

"Marc and Jim have

a relationship with Sokol," Rankin said. "They know the

ins and outs of the facility. There are plusses and minuses to partnering

on promoting a show. There's less money to be made, but if the show

doesn't do what it's supposed to do, the risk is minimized."

Rankin said he's never

butted heads with 1% on a potential show because the two organizations

share a similar goal. "Neither one of us meddles in the other's

business," he said. "There are shows we both might have

an interest in, but we have discussions and it comes down to what

venue makes the most sense. We're similar in that we want these

artists to come to town regardless of who's making the profit."

However, the risks are

becoming greater for 1% as it pursues more and more bigger-name

shows for Sokol Auditorium, such as their June 13 Dashboard Confessional

show that was, for the most part, a success. A lot hinges on this

month's busy auditorium schedule, which also includes Guster July

9 and Chevelle July 18.

"The break-even

number for upstairs shows is a lot higher," Leibowitz said.

"In addition, it's an all-day thing. We have to get there at

10 a.m. and help load in, get them a catered meal, be there at sound

check. It's just a much bigger deal and a lot riskier.

"Through the end

of July, we'll have had five shows in five weeks upstairs at Sokol.

If all of them tanked, 1% would be done. It's not like we have all

this money in a bank account. If we lose, it comes out of our pockets."

But one upcoming 1% auditorium

show that's a sure thing is Saddle Creek act Cursive August 10.

When interviewed by Vogue magazine recently about 1%'s role in the

booming Omaha scene, Leibowitz modestly denied the connection. "I

told him the only thing we're responsible for is Sokol being successful

and for getting the Saddle Creek bands to play somewhere other than

The Cog Factory."

But Robb Nansel, who

heads Saddle Creek Records, disagrees. "For Leibowitz to say

he had nothing to do with it is a fallacy," Nansel said. "Anyone

who's been involved with venues like Sokol Underground or The Junction

has helped build awareness about this kind of music. Marc's gone

out of his way to get quality bands like Wilco to play here -- something

that never could have been done without him. It gets everyone who

listens to music excited about what's going on here and creates

awareness for the bands and the scene.

"Independent promoters

are important and necessary for any scene. We need even more people

promoting rock shows around town."

Rankin agreed. He said

independent promoters are critical to keeping any one entity from

monopolizing the marketplace. "It's supply-and-demand economics,"

he said. "If you only had one entity providing entertainment

in this town, you'd see a whole lot of country and western bands."

You certainly wouldn't

be seeing acts like Cat Power.

In a ritual that caps

off all evenings at the Sokol, Leibowitz and Johnson disappear with

the cash till and count their takings. They pay their sound man,

pay the bands, and deposit the rest in their joint account. For

Cat Power, there wasn't much left over, but at least they didn't

lose anything and Johnson got to see one of his favorite bands.

For the last chore of

the evening, the two take their positions on the stairway leading

out of club and hand out fliers that list upcoming shows.

"We started 1% because

we wanted to start our own company," Leibowitz said. "We

wanted to do our own thing. The company's name comes from a Jane's

Addiction song and was inspired by one of their lyrics: 'I'm tired

of living the bosses' dream.' The end game is still to own a club,

but we're in no big hurry. We're doing okay."

Back to

Published in The Omaha Weekly-Reader July 9,

2003. Copyright © 2003 Tim McMahan. All rights reserved.

|

Guster

performing at the larger Sokol Auditorium.

| |

"If

you only had one entity providing entertainment in this town,

you'd see a whole lot of country and western bands."

|

|

|

|