Fresh from signing a 7-record deal with Capricorn way back in

1993, 311 had dreams of making it big. Who could have guessed just how big they'd make it?

|

|

|

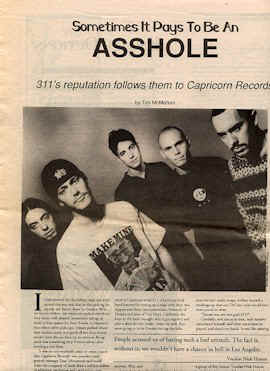

Sometimes It Pays to be an Asshole

by Tim McMahan

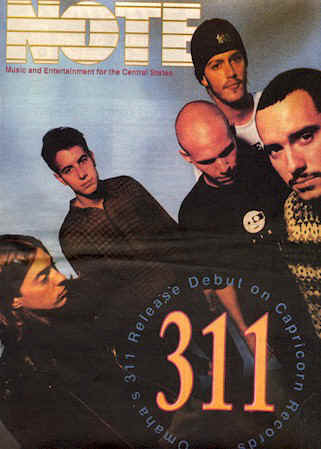

| Tim writes... This story was written way back in February 1993 and was published in The

Note, a music magazine out of Lawrence, Kansas, that called itself "music

and entertainment for the Central States." Everyone knew who 311 was at the time. No

one knew for sure what would come of their record deal with Capricorn. You were either in

the camp that they were destined for stardom, or you thought they were shamelessly ripping

off the Chili Peppers. The rumor that was going around at the time was that Flea had

cornered Hexum and told him to quit aping his band's style. In retrospect, it was probably

bullshit. The fans know that the band didn't exactly rocket to stardom after their first

album. It wasn't until one of their videos received heavy rotation, and they got a spot on

the Vans Tour, that things started happening. Now their huge, of course.

It should be noted that The Note was really written

with the musician in mind. Editor Jeff Shibley loved writers to get the inside industry

scoop. Hence, there's a predominance of detail from the execs at Capricorn (I think Shib

thought he was doing bands a favor by showing them the ins and outs of the biz, who

knows.) I did a follow up story a couple years later, again for The Note. This time the

interview took place on the band's tour bus -- they were big time. That one included some

details from Gold Mountain, who had just dropped the band (or was it the other way

around?) and also included some Nick commentary on specific producers he didn't like

working with... and so on. If there's interest out there, I'll also post that story.

Oh yeah, the headline here is as it appeared in the

publication (page down a little further and you'll see). I remember Nick saying he liked

it. His step mom, Pat Hudson, who I interviewed a few years later, didn't seem to mind the

headline, either. |

|

|

It had snowed

the day before, and cars were parked this way and that in the parking lot outside the

Ranch Bowl in Omaha. With no lines to follow, the motorists parked anywhere they damn well

pleased, sometimes taking up three or four spaces for their Buicks or imported

4-wheel-drive pick-ups. Others parked where they landed, stuck in a patch of ice; they

would sooner leave the car than try to move it. Being stuck was something they'd worry

about after blowing a few lines. It was an unremarkable place to meet a band that

Capricorn Records' vice present and general manager Don Schmitzerle said could drain the

company of more than a million dollars in advances, marketing and production costs before

it was all said and done ("but it's not a million-dollar deal," he was quick to

add).

The Ranch Bowl is essentially a glorified bowling alley that's been turned into a music

venue, while retaining enough lanes to service any good-sized league play. Tonight's

entertainment is Capricorn artist 311, a hardcore funk band known for tearing up a stage

with their two rappers and three instrumentalists. Formerly of Omaha and now of Van Nuys,

Calif., the boys in the band thought they'd get together and play a show for the locals

– what the hell, they were going to be in Omaha visiting the folks anyway.

I met them that afternoon during a break in their sound check. There they were, sitting

in the back of the bowling alley, looking like any other table of local college kids in

for a few games of pinball, scoping out the Betties. Except maybe for P-Nut, the bassist

– his dreadlocks made him look like a wet cat pulled out of a pool. He kept the hair

under wraps, hidden beneath a stocking cap that any Def Jam artist would have been proud

to wear.

"Excuse me, are you guys 311?"

Cordially, and one at a time, each member introduced himself, said what instrument he

played, and shook my hand. It was like meeting a group of Boy Scouts. Vocalist Nick Hexum

took the lead on most of the answers, but looked thoughtfully around the table to see if

any of his bandmates had any comments.

Later that evening, after the article's photo shoot, drummer Chad Sexton had spied a

folded T-shirt lying on the counter in the studio. He liked the logo on the front, and

asked photographer Mike Malone if he could wear it for the photos. Afterward, Sexton

stripped off the shirt and folded it carefully as a clerk in a K mart store. "Thank

you very much for letting me borrow your shirt, Mike," he said meekly to Malone, who

later commented that Sexton seemed as well-mannered as a stray dog brought in from the

rain.

It was all shocking behavior from a band that has a reputation for being a bunch of

assholes. Omaha music "insiders" and members of other band have told me that

that's exactly what these guys are. Everyone seems to have a dirty 311 story that he's

dying to share, and all of them seem to come down to "Nick is mouthy, and the rest of

the guys are arrogant jerks."

Hexum addressed the "asshole factor: this way: "Folks in Omaha have been

great supporting us, but we've been faced with a lot of assholes, too – bands

downtown who really wanted to keep us out. We were viewed as young upstarts. People

accused us of having such a bad attitude. The fact is, without it, we wouldn't have a

chance in hell in Los Angeles.

"It's really hard to get attention," Hexum continued, raising his voice above

crashing bowling pins and PA announcements. "We're just starting to get fans out

there. In Omaha, we had a great fan base. In L.A., we only do occasional shows. It's

tough, there's so many bands."

"People out there can't believe we're from Omaha, that our sound came from

Nebraska," P-Nut said. "It gives us a leg up."

"We're not the product of some scene," Hexum added.

"We're proud to be from Nebraska," vocalist SA said. "We're from here,

we're not diluted from being from somewhere else. Growing up here was sweet. It was a

nurturing environment, especially the crowds."

Does Hexum feel the pressure to be a success? "We're pressuring them," he

said, then hesitated, adding, "No one's pressuring anyone. We recorded this album way

under budget and under schedule. We're doing our own thing.

"You've got to be relentless," Hexum said. "My advice to any young band

is that if you're not sure you have what it takes, give up. Only the truly dedicated are

going to make it in this business. Back in high school, I used to tell everyone that I was

going to make it. If you're not sure about yourself, your chances are slim and none."

Now there's some attitude for you. |

"We were viewed as young upstarts.

People accused us of having such a bad attitude. The fact is, without it, we wouldn't have

a chance in hell in Los Angeles."

|

|

Picture this:

two or three hundred kids (average age 16) packed onto a dance floor moshing, jumping up

and down and "crowd surfing" – kids were floating above the crowd on an

ocean of raised hands until, sometimes brutally, they fell flat on the floor.

On stage, all five of 311 were shirtless, covered with sweat, bouncing off each other.

Hexum and SA were in the midst of a mighty rap duet, screaming their defiant lyrics to a

frolicking mass that couldn’t care less what they had to say because they were too

busy jumping up and down to pay attention. It was as strange as being in the center of

some Middle Eastern religious ritual.

I asked the guy next to me what he thought of the band. "I hate this kind of

music," he yelled, hurting my ear. "but I've got to admit, this is a

blast."

A key to success: even people who hate this music are going to get caught up in the

energy of the band's live shows.

311's rap that night was tight, the bass was sterling, drums were on the edge, guitars

were sometimes heavy, sometimes jazzy, and the vocals interlaced as well as any young

top-ranked rap act.

They're not your typical rock 'n' roll band, but neither are the Beastie Boys or the

Red Hot Chili Peppers, two outfits that 311 most closely resemble and to whom 311 don't

like to be compared. In fact, they say they don't like to be compared to anyone, though

even to the most casual listener, 311 sounds like a trashier version of some white college

rap acts you've seen on MTV. |

|

"I don't think arrogance is a valuable

asset for any band to have, but in order to succeed in the music business, it's the bands

and the artists that want it more than most that really pull through. There are a lot of

artists vying for air time. Nick was very enterprising."

|

Vocalist

Hexum, guitarist Timothy J. Mahoney and drummer Sexton formed their first band, Unity,

after they graduated from high school in 1988. They played at a number of Sunset clubs in

L.A., then broke up, moved back to Omaha and reformed as 311 with bassist P-Nut and

vocalist SA.

But after many gigs and three tapes on their own label, 311 didn't seem to be going

anywhere soon. They had sent the tapes out to a handful of record companies before moving

back to Van Nuys. Then one day, one of the tapes found its way to Capricorn Records, a

division of Warner Bros.

"(Signing 311) was a decision that involved the entire company," Schmitzerle

said. "The tape actually came from an associate. Eddy Offord somehow got ahold of it.

He's been in the business for a long time, producing Yes's early albums. Eddy had seen 311

once in Los Angeles. When I discovered Eddy was involved, that made the deal much more

attractive."

With little fan support in L.A., the band knew there was only one place to woo

top-brass A&R guys – back in Omaha. A show was quickly set up and Schmitzerle

flew in. The ploy worked.

"They own that town," he said, winding up for a big spin. "That night,

they had a real spark. It wasn't the rap that turned my head, but the fact that they did

so many things so well. They do a little reggae, some funk, but the very essence of the

band can't be labeled. I saw them as part of a larger whole."

Ah, but what about the asshole factor?

"I have to admit, I like Nick's take-no-prisoners attitude," Schmitzerle

said. "I don't think arrogance is a valuable asset for any band to have, but in order

to succeed in the music business, it's the bands and the artists that want it more than

most that really pull through. There are a lot of artists vying for air time. Nick was

very enterprising."

According to Schmitzerle and 311, the band was practically signed on the spot with a

seven-record deal – two albums and five one-year options.

They took the contract and quickly entered Ocean Studios in Burbank. And behind the

knobs was Eddy Offord, the Yes producer who also worked with John Lennon, Billy Squire and

the Dixie Dregs. It took them two months to record their first CD, Music, slated

for release on Feb. 9. The 12-song release does a good job of catching the band's energy

– it's one part Beastie Boys, one part Bob Marley, one part Chili Peppers.

But getting on the air is going to take more than a pouty attitude. How well is 311

going to adapt to industry showcase gigs like the one they recently played over the lunch

hour at a warehouse in Burbank? Surrounded by music industry-types in sportcoats and ties

who were holding half-empty cocktails and tiny sandwiches served on frilled toothpicks,

the band did their best to convince an unknowing, uncaring audience that they were the

"next big thing."

"For an artificial situation that doesn't duplicate crowd energy, the band adapted

very well," Schmitzerle said. "I'm sure it was strange for them seeing all those

suits staring back at them."

The lunchtime show was good enough to impress reps from Gold Mountain, a management

group that handles Nirvana, Bonnie Raitt, and yes, the Beastie Boys. With Gold Mountain on

their side, all the band needs now is an agent to book shows.

But changes are they'll be staring at those same suits at their next gig: the Gavin

Convention. "Bill Gavin publishes a radio tip sheet and hosts and annual convention

that draws a good cross-section of people, Schmitzerle said. "It's a golden

opportunity."

The three words here are sell, sell, sell. Mark Pucci, Capricorn's vice president of

publicity, said the label is currently trying to get 311 written up in the right

publications – line The Note, he added like a real PR pro.

"We've had good response so far," Pucci said. "Once the band gets on

tour, we'll work hard to support their dates and set up advance interviews with the

media."

Schmitzerle agreed. "We have to press the predictable buttons, but our main focus

is supporting the touring activity. We'll work this record a long time. We're going to

take our time and build from the ground up."

And don’t forget national television. Pucci said he's trying to get 311 on TV

shows like "Arsenio." "Our job is to get them seen on videos, television,

radio and live performances," he said. "No matter what we try to do to

encapsulate their image, it's up to the band to deliver. And this band does."

To top it off, Pucci said a great deal of 311's success could depend on, well, the

asshole factor.

"The band has an aggressive attitude, especially Nick," he said. "You

have to have that, because it's tough to go from getting attention in Omaha to getting

attention nationally. Their work is really just starting. They have the rest of the world

to conquer. They'll have to work their butts off as performers, songwriters and musicians;

be able to handle interviews, deal with retail people and deal with the internal

organization here at Warners.

"When a band gets signed, they might think they've made it, but the work is just

beginning."

Originally printed in The Note, February 1993.

Copyright © 1999 Tim McMahan. All rights reserved.

Photos by Mike Malone, Copyright © 1999 Mike Malone. Used by

permission.

Back to  |

|

|

![]() webboard

interviews

webboard

interviews