They were

married their senior year and graduated together from UNL in 1950 (they celebrate their

50th anniversary Dec. 27). It's almost impossible to talk about Bill Farmer and his work

without thinking of Margie. Her work was responsible for most of their travels, as she was

called to set up Montessori schools in countries throughout the world, including Spain,

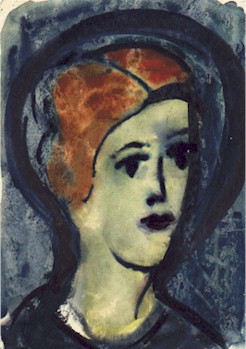

Ireland and Mexico. While in Spain in '53, Bill studied the works of El Greco and Goya. He

says their work,continues to influence him to this day, along with the art of Max

Beckmann, who Farmer studied under at the University of Colorado in 1949. "I was

chosen to be in Beckmann's class when my name was drawn from a hat," Farmer says.

"He didn't speak much English. He always said, 'ya, ya…' He had quite an

influence on me. I suppose expressionism crept in from Beckmann. He always had something

to say in his work, and that inspired him."

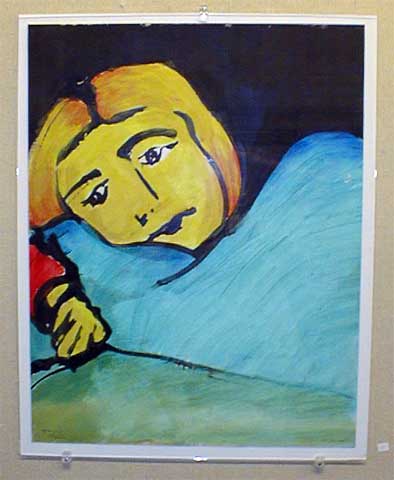

Farmer also speaks through his work, whether it be a political or spiritual statement.

"Spirituality and social commentary are my two strongest themes," he said.

"If I didn't like something, I would paint it. I painted against Castro for killing

freedom. I don't feel that way today. Now I think socialism is good if practiced

religiously."

He talks about how he painted on large sheets of paper in the streets of Mexico, of

trading art lessons for art supplies and painting on the interior walls of their home on

42nd and Burt streets when there was nothing else to paint on. "On one wall, I

painted Mary and the Women of the Well. In the front room it was the Good Shepherd. The

landlord was rather pleased; he took a door I painted off the kitchen cupboard and took it

home."

He first dabbled in abstract painting while studying at Cranbrook Academy of Art in

1951 and was among the first Omaha artists to attempt abstract multimedia presentations.

"I put on something called 'The Event' in 1968. It included 16 mm, 8 mm, and slide

film, actors in a boxing ring, anti-meetings and anti-church. It was a social criticism

and was well publicized at the time. Very disturbing. I didn't know how they'd take

it."

He says it never really mattered to him if his work was accepted. And that is probably

the reason the Farmers never got fat off Bill's art. "We always just had

enough," Margie says. "We just kind of alternated -- sometimes I was not

working, sometimes Bill wasn't working. But we always had enough between the two of

us."

These days, Farmer produces less art then in his youth, though he continues to use

innovative methods to convey his ideas, such as concrete sculpture. Parkinson's symptoms

and bouts of anxiety have slowed him, he says. "These days I usually start my

drawings in the afternoon on the front porch. I work a couple three hours a day more or

less, depending on what else I have to do. I used to work 'til 11 at night. I have to

strain for it today.

"My work remains a way for me to continue to speak out. Certainly the same

injustices are evident in the world today, maybe even worse than ever before. When I look

back at my lifetime of work, I'm satisfied with what I've accomplished."