|

|

|

|

| This is the third part in an ongoing series that

traces the ups and downs of Grasshopper Takeover, a power-pop rock band formed in Omaha. Part 1, published July 9, 1998, documents the

band from its origins to its flight from Omaha to Los Angeles. Part 2, published Dec. 23, 1998, recaps the band's

first months in L.A. and their struggle to play on the Sunset Strip rock scene. |

|

|

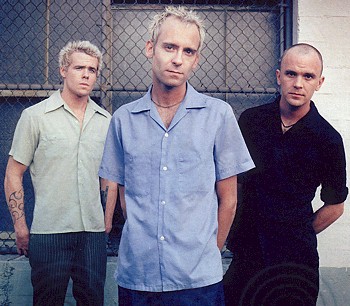

Grasshopper Makeover After a couple years in L.A. and months on the road, the former Omaha

pop-rock phenoms have a new definition of success.

by Tim McMahan

First thing's first. Before I

sat down with Curtis Grubb, head honcho and one-third of the formerly Omaha-based pop

rockers Grasshopper Takeover, we agreed that we would not focus on the old news that the

band has moved from Omaha to Los Angeles. The approach was my idea, having already written

one going-away story about the band, followed by a "how's L.A. treatin' ya?"

story five months later.

They moved. It's been two years. Get over it.

The new approach: Treat GTO (shorthand for the band's rather arcane name) like any

other band that's traveling through town, stopping in Omaha as they cross the country on a

rock-n-roll pilgrimage.

Grubb couldn't be more pleased with the new tactic. "A lot of people still dwell

on the L.A. thing," he said. "We haven't been there in three months. We've been

on the road since April 14 and won't stop until Jan. 1."

Nine months on tour? Egad!

It should be noted that this isn't the same beer-guzzling, video-golf playing Curtis

Grubb we paid fond farewell to just a couple years ago. It's a new, entirely different

looking Grubb, with mod spiked hair, yellow wrap-around hunting-style safety glasses,

headband, black shirt and trousers. Very hip for a guy from Omaha.

We met at the laid-back La Buvette wine bar and grocery in the heart of the Old Market,

just a block or so away from the Howard Street Pizza and Pub joint, where in a few hours

Grubb and his band -- drummer Bob Boyce and bassist James McMann -- would be hosting an

appreciation pizza-feed for their local supporters.

As Grubb took a seat, an old acquaintance at a nearby table spotted him and said hello.

"At first I thought you were one of those Bemis people," he said. Grubb just

smiled; acknowledging the reference.

Grubb insisted that we share a bottle of wine during the interview. "Do you have

Chateau St. Jean?" he asked the waitress.

She looked back, blankly. "I don’t know. If we did, it would be somewhere in

this pile of French wines," she said, pointing at a couple of carefully overturned

bottle-filled crates. After a brief search, the two agreed that they don't have Chateau

St. Jean in stock. Grubb disappointingly asked for a nice red instead, and nodded

approvingly at the waitress's recommendation. |

|

|

After we got

to talking, it was clear the road or L.A. had changed more than Grubb's fashion sense and

taste in fine wines. Just two years ago, the band left Omaha with stars in their eyes,

destined to sign a mega-deal with one of the industry's major record labels. Grubb used to

scoff at the idea of being in a band to "just raise enough money to record and play

shows."

No more.

"Sure, we'd like to get signed, but right now we're doing everything we can to

prove ourselves to the industry and the fans," Grubb said. "A lot of people

still ask me why we haven't signed a contract. The contract is secondary to what were

doing now. From the beginning, our goal was to play our music and tour the country. The

last thing I want to do is worry if the industry is going to like us or not."

He took a sip of wine and lit another in what would be a long series of cigarettes.

"It was our objective to get a deal when we moved to L.A.; now it's the

opposite," he said. "L.A. was a good place to build a team, and now everyone

around us wants to see us succeed. The money part is secondary, as long as we have enough

to do what we're doing. We're selling units and gaining a serious underground fan base. If

you don't have a fan base, you're not going to sell CDs anyway. You might as well build it

first. A lot of label shit is egos and cock fights, all the way into upper

management."

While it might read as being defensive, Grubb actually comes off as someone who

genuinely believes in what he and his band are doing. He's convinced they are exactly

where they want to be -- not signed to a indentured-servant-style 9-album deal with a

major label that would work them like pack mules.

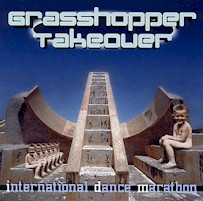

Instead, the band is touring their International Dance Marathon full-length CD,

put out earlier this year by the locally based independent label, Redemption Recording Co.

The 12-song collection of catchy pop-rock ditties is easily the finest recording the band

has ever put out and includes production credits by the likes of Gabriel Mann and 311's

Nick Hexum and Chad Sexton. Without the support of a major label or distributor, GTO will,

for the most part, distribute the CD via the Internet and the merchandise tables set up at

show after show after show. |

|

"Without sounding like an asshole, I

don't feel sorry for bands that sign these multi-album deals with a 10 percent royalty and

no creative control."

|

"Our

tour can be summed up in one guiding phrase: If you build it, they will come," Grubb

said. "Living out in L.A., we've come across people who we're comfortable surrounding

ourselves with; who we can trust. They're involved in all facets of our tour, from

publicity to radio to distribution to merchandising, financing and accounting. My mom

(Linda Grubb) is the centerpoint for everything. She's GTO Central."

The traveling carnival works this way: The band's agent, Duffy McSwiggin, books the

entire tour about three weeks in advance of wherever the band is playing at a given time.

Grubb receives the faxed contracts on the road. Linda then sends out advance packages to a

team of 15 or so support staff. Each has a job to do, from sending materials to venues to

contacting the band's "street team."

Street teams have become a common practice among a number of touring rock bands.

They're made up of local fans who do it all, from flyering the shows to contacting radio

stations requesting to hear the band's music -- all for the glory of being able to call

themselves "insiders."

"They are everything to us," Grubb said. "They're our eyes and ears. Put

yourself in the position of being a 15-year-old kid working with a band you love, and

corresponding with them and their family. We give them laminates to get into all of our

shows for life. We send them birthday cards. They are part of our team. The network is

nationwide -- we have 60 people in 40 to 50 cities. It's part of how you do business these

days. You have to have it."

Still, street teams can't fill up the van's gas tank before the band heads out on the

road for eight hours to the next gig. Touring is an expensive endeavor, and to help

support their tour financially, Grubb worked with some industry folks, including a contact

at Universal (now Farm Club), and Maverick Records CFO Ike Yoseff, who "gave us the

means where we wouldn't have to spend thousands of our own for tour support," Grubb

said.

"We sell CDs and T-shirts everywhere we play," he said. "We can bring in

anywhere from $100 to $300 a night in merchandise in the Midwest markets -- enough to keep

us alive on a day-to-day basis. It's all very doable, but you have to set yourself up

ahead of time. Bands who try to do this without a network of fans… Well, it just

doesn't happen."

Road manager John Cardell documents unit sales with Soundscan, the industry's sales

tracking system. Since the tour began, Grubb said the band has sold more than 3,500 copies

of International Dance Marathon. It's a long way from the 20,000 or so he thinks he

needs to move to get the attention of the industry, but it's a start. Add to that a

5,000-name e-mail list and the fact that his website -- www.grasshoppertaker.com -- is garnering about a 1,000 hits a day, and you've got a movement afoot.

"Every label is after a one-hit wonder that will last about a year," he said.

"It's a beautiful thing to have gradual progress and momentum. Without sounding like

an asshole, I don't feel sorry for bands that sign these multi-album deals with a 10

percent royalty and no creative control. The label brings on the girls, cocaine, limos,

whatever it takes, and they get wooed by it. The label will make their $2 million and the

band will end up in debt. And at the end of the day, the band hates itself and asks, 'Why

did I sign my life away? We had a good thing going.' I'm not willing to give up 100,000

hours of work to someone because they promise the world. It's not fair to me and the band

and the people around me."

While most people would consider the definition of "paying your dues" as

living with three people out of an equipment-packed van for nine months, Grubb considers

the situation a dream come true.

"Paying your dues is a double-edge phrase," he says. "It assumes that

you are getting it in the ass now in hopes of getting something better. Right now I'm

happy as can be being on the road and playing the music. If this is paying your dues, I'd

hate to see what the phrase really means. We're happy with where we are because we're

growing every time we play another show. If we weren't building a fan base, we'd probably

break up. That's why we had to get out of L.A. When it gets stale, you have to get the

fuck out of town." |

|

|

His only

gripe about the constant touring is the crimp it's made in his songwriting efforts. Though

he continues to make daily entries in his personal journal and has devised a system to put

melody to paper, Grubb said writing music on the road is his toughest challenge.

"You get all this built-up creativity, but there's hardly an hour in a day to work

it out," he said. "You drive, unload, soundcheck, sit in the bar, play, meet

people, and leave at 2 a.m. The last thing you're going to do after all that is pick up

your guitar."

Regardless, when the tour ends in January, Grubb and company plan to hole up in their

Burbank, Calif., rehearsal space and put together an album based on their road

experiences. "We'll have three months to write and record the next album before we go

on tour again. It's like setting a wedding date -- you have no choice but to be

ready."

It turned out that Grubb really hasn't changed that much after all. He still has the

same sunshine-filled outlook he had the day he left Omaha to chase his hopes and dreams in

Los Angeles. In fact, maybe the most amazing thing about him and his band is that they've

managed to keep such a positive attitude despite all the barriers they've had to overcome.

"It's taken us a long time to get to this point," Grubb said, as he finished

off the last of the tasty port and lit one last cigarette. "You can't get jaded by

doing your own thing. The trick is to not get involved with people who say they'll do

something and then don't follow through. Don't get involved with promisers.

"So many bands break up by looking to the labels for their future. You just have

to do what you do and be happy about it. It's tough, but you have to say to yourself, 'I'm

playing music and affecting thousands nationwide. I've got an album out. I'm not starving.

I'm healthy and my family is healthy.' You have to have a positive attitude and have good

laughs on the road so that you can look back when you're 70 and can say, 'When I was 25 I

was doing what I wanted to do.'"

Back to

Published in The Omaha Weekly July 27, 2000. Copyright © 2000 Tim

McMahan. All rights reserved. |

"You drive, unload, soundcheck, sit in

the bar, play, meet people, and leave at 2 a.m. The last thing you're going to do after

all that is pick up your guitar."

|

|

![]() webboard

interviews

webboard

interviews