|

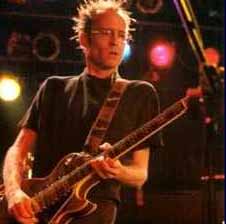

Grasshopper

Takeover:

There and Back Again

story by tim mcmahan

| |

|

Lazy-i: March 24, 2004

|

Grasshopper Takeover

w/Lucky Boys Confusion, Swizzle Tree, more

March

27

Sokol Auditorium

13th & Martha

5 p.m.

This

is the fourth part in an ongoing series that traces the ups and downs of

Grasshopper Takeover, a power-pop rock band formed in Omaha.

Part

1, published July 9, 1998, documents the band from its origins to

its flight from Omaha to Los Angeles. Part

2, published Dec. 23, 1998, recaps the band's first months in L.A. and

their struggle to play on the Sunset Strip rock scene. Part

3, published July 27, 2000, catches up with the band during a brief break

on their 18-month national tour.

| |

| If this was

an episode of VH-1's Behind the Music, Omaha rock band Grasshopper Takeover's

life story would be somewhere past the third commercial, after the inevitable

downfall and Phoenix-like return from the ashes. Literally. But

we're picking it up after the second commercial, back in July 2000 when our heroes

-- guitarist/vocalist Curt Grubb, drummer Bob Boyce and bassist James McMann (guitarist

Michael Cioffero had yet to join the band) -- were just beginning a nationwide

tour expected to last nine months. The world was their rock 'n' roll oyster with

a home base in sunny Los Angeles where they'd moved two years earlier to be closer

to the rock industry. "We were still living there in '99, but we're

getting ready to go on tour," said Grubb over coffee at Caffeine Dreams.

"You mentioned a 9-month tour. It was more like two years. It lasted from

the end of 1999 until about 2002. After 18 months on the road, we decided to give

up the L.A. apartment and rehearsal space." It wasn't the classic tail-between-the-legs

"retreat" that has scarred so many other bands that followed the yellow

brick road to that famous beckoning Hollywood sign only to be told that they couldn't

get a meeting with the man behind the curtain. Grubb said the move had more to

do with following the target than leaving it behind. "The same philosophy

applied then as now: I go where the music takes me," he said. "The reasons

we didn't go back to L.A. were financial and creative. You get off the road after

18 months and there's not a lot of money in the bank. "We figured if

we go back there it's going to cost $8,000 just to get reestablished, and $2,000

a month to live in our place in Echo Park. Or we come back to Omaha and put together

a studio. If we're artists, we can create anywhere. We don't need the California

sun as a catalyst."

|

| |

The band already had gotten almost everything

they wanted out of L.A. anyway, from meetings with high-level A&R people including

the CFO of Universal Records, to gigs at Sunset Strip clubs and a booking agent.

But the big-time record label deal remained elusive. "We had interest,

but our guiding philosophy has been to stay on our own path, sometimes to our

detriment," Grubb said. "Even the CFO wanted us to stick around L.A.

and do showcases, but we wanted to tour." Their willingness to live

on the road eventually got them the arena-sized gigs that they always dreamed

about -- opening for old friends 311 and the insanely hot Incubus as part of a

Levi's-sponsored tour in early 2001. Once the tour was announced, GTO's

exposure went to a whole 'nother level. "We started getting hundreds of e-mails

a day. It was an explosion that lasted before, during and after we stepped on

stage," Grubb said. Halfway through the 311/Incubus tour, Atlantic

Records offered GTO a "demo" deal that would put their song, the bouncy

pop tune "Esta Vida," on a compilation CD next to songs by some of the

country's hottest acts. But GTO turned it down. "If it didn't work out, we

were still contractually tied to Universal for two years. It would have been like

hitting a bull's-eye in a blackout in a snowstorm with a b-b-gun from 200 yards

away." Atlantic would be the last major to come knocking, which came

as a surprise to GTO and their fans. In retrospect, Grubb says the band's music

isn't easy to categorize, which makes for tough marketing. "The songs we

play that should be on the radio don't fit the format," he said, adding that

even their heavy songs, like the fan favorite "Bone Crusher," aren't

raucous enough to be heard on stations that play Korn and Limp Bizkit in heavy

rotation. Grubb said six years of recording and touring have yet to net

GTO the big payday that they used to think was just around the corner. These days,

the band that dreamed of being as big as U2 has set its sights a bit lower. "It

would be nice to put something in the bank for myself," Grubb said. "We've

never paid ourselves over the years. Every penny has gone to the Grasshopper Takeover

bank account. There were times when we had so much money but still didn't pay

ourselves. Like any small business, you need to treat your income as one step

further into your next venture. If you have $10,000 in the bank, that's enough

to buy more T-shirts and 3,000 CDs." Regardless, making money has never

been the band's No. 1 goal. "As cliché as it sounds, if you're not

doing it for the music, get out now," Grubb said. "It's pretty hard

to find three guys willing to stay together for seven years without seeing a dime.

It let's you know that you have something special. "It would just be

nice to get paid someday, but if I don't, I can't not write songs. Maybe I won't

be famous until after I die, and when I'm gone, I'll leave a legacy of music."

|

|

"It's

pretty hard to find three guys willing to stay together for seven years without

seeing a dime. It let's you know that you have something special."

| |

| |

| |

"If

we're artists, we can create anywhere. We don't need the California sun as a catalyst."

| | |

Music like the band's recently released

album, Elephant Dreams, the product of a new $15,000 home studio that provided

unlimited time and resources for recording the CD's 19 tracks. "We've

always gone into the studio and recorded songs exactly as we played them live.

We had no money for production ditties," Grubb said. "This time we could

spend a month on a song. Instead of nailing the drum part in 30 minutes, we could

spend two weeks on it. It would have cost us over $100,000 in studio time. Having

the freedom to put an album like this together is the best thing to happen to

us on a creative level." But sometimes having no limits isn't necessarily

a good thing. "You have to set an absolute deadline with that kind of freedom,"

Grubb said. "We set the date for the CD release party and started promoting

it so we couldn't go back on it. We still had three songs to record, so we cranked

shit out the final three or four months. In classic fashion, we got the CD the

day before the show." The Nov. 26 concert at Sokol Auditorium sold

out, just like the band's farewell show at Sokol almost six years earlier. In

addition, that evening GTO sold more than 1,000 copies of Elephant Dreams

-- a concept CD that in part recounts the band's all-time low -- when their tour

van was stolen loaded with $25,000 of equipment -- an incident that couldn't have

happened at a worse time. "We were at a point where the crowds were

dipping at our shows, kind of like an old girlfriend that you still love but don't

want to sleep with every night," Grubb said. "It had been two years

since we put out a CD and the fans were wondering if we were still in the game.

The reality was that we had our noses to the grindstone trying to get the next

album out." When their van was stolen literally before their eyes it

was "a total loss and total violation," Grubb said. "People thought

the whole thing was a publicity stunt. I'm thinking, 'Thanks for the compliment.'

If I had the power and expertise to pull a stunt like that, it would be pretty

amazing." The aftermath -- the van being burned up, the return of their

gear, and the donation of a new van by local newsman Dave Webber -- was covered

closely in the local media. So much, in fact, that sound bites from TV and radio

reports were woven between some of the songs on Elephant Dreams. "We

couldn't not do it," Grubb said. "Every band is supposed to have a story.

This documents ours." Clocking in at over 70 minutes, Elephant Dreams

easily is GTO's most ambitious and musically varied recording. The music sounds

like the feel-good stadium rock that you used to hear on the FM in the '70s and

'80s. Big guitars playing big riffs on songs with big hooks sung by Grubb in his

slippery midrange voice that has just enough polish to remind you that he's not

indie and doesn't want to be. There are certain elements that are oddly modern

amidst the usual guitar bombast. But the rhythms and melodies are pure heavy pop

rock -- not pop-punk, not trip-hop -- just plain rock, born from the minds of

four Midwestern guys who grew up loving the bands they heard on the radio. Pure

fun, with no regrets. A self-released CD, GTO recently signed a distribution

deal with Harvest Media Group. Needless to say, a tour will follow. So

will their story have a traditional fame-and-fortune Behind the Music ending?

Only time will tell, though Grubb would just be happy if the story never ended

at all. "I don't want to think small, but it would be nice to sell

10,000 copies of the new CD and create five or 10 markets for us," Grubb

said. "It would be nice to be able to put some money in the bank and be able

to tour for a long time. "It would also be nice to sell 10 million

copies. But we know where we are as a band. The idea of getting picked up by a

major label is fantastic, but it never guides anything we do anymore. As a result,

the music becomes more pure in that it is just a piece of art we hope to survive

on. Beyond that, everything is a bonus."

Back

to  Published

in The Omaha Reader March 24, 2004. Copyright © 2004 Tim McMahan. All rights reserved.

| | |

| | | |